October has a lot going for starwatchers and other appreciators of nature at night. Never mind this weekend’s rain; October nights are especially clear on average. Darkness arrives early, the hazes and mosquitoes of summer are mostly gone, but it’s not yet winter.

So what’s to see up there these evenings? It depends where you look.

The whole southeastern side of the sky appears almost blank through the light pollution inside Route 128. This celestial realm is known as the Great Water, home to big, dim, water-themed constellations: Capricornus the Sea Goat, Aquarius the Water Pourer, Pisces the Two Fish, and just nosing above the horizon, Cetus the Whale.

Good luck picking them out.

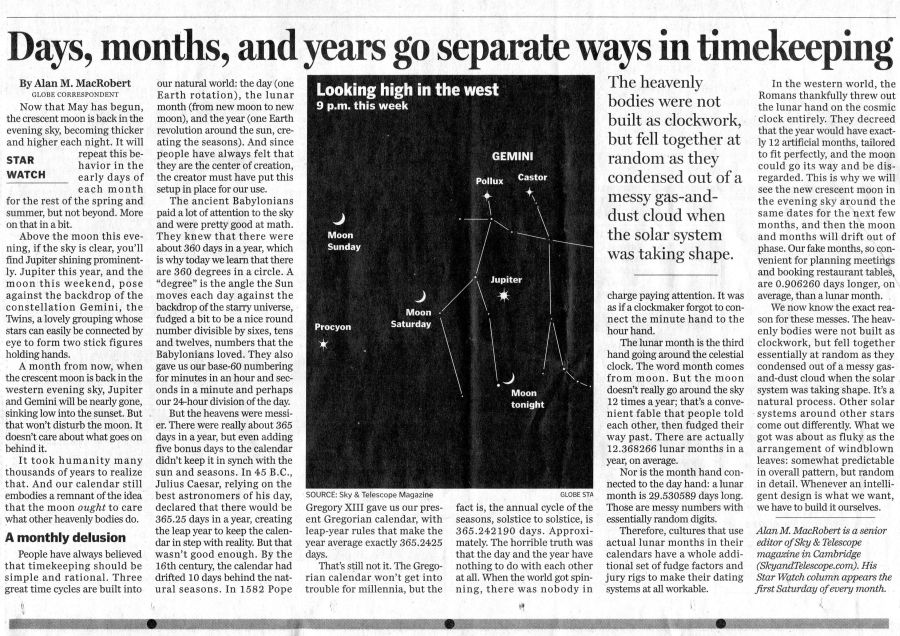

Elsewhere things are more interesting. Turn east and face high, and unless your light pollution is truly awful, you’ll find the Great Square of Pegasus, emblem of fall. It’s part of the flying horse of Greek myth.

Look for a square a little larger than your fist held at arm’s length, tipped up onto one corner.

The Square is supposed to be the front half of the horse’s body. Save the rest for a night in country darkness.

From the square’s left corner, a line of three or four stars extends left and slightly down. This is the profile outline of Andromeda, damsel in distress of Greek legend. The left-corner star is her head, the rest of the line is her backbone and one leg, the other, dimmer leg is raised and bent at the knee, and her outstretched arm is supposed to be chained to a rock. We’ve drawn her whole big stick figure in case you have a dark enough sky to piece it out this week or next.

Andromeda is most famous for what’s just off her upraised knee. Look for a hazy little dim-gray glow, like an escaped oval tuft of Milky Way.

The tuft looks like that for a reason. It’s the Great Andromeda Galaxy, an approximate twin of our own Milky Way Galaxy but 2.5 million light-years distant. If any creatures there have eyes like ours and clear nights, they’re seeing our own galaxy looking about like that.

A pair of binoculars makes it easier to spot, but even the view in a telescope is underwhelming from Eastern Massachusetts. It doesn’t look like the enormous thing, striped with two black bands, that 19th- century astronomers drew before photography revealed its true form.

Last summer I got a proper view, black stripes and all, from the Summer Star Party — a big annual amateur-astronomy gathering in Plainfield, in the dark northern Berkshires. A group of New York amateurs brought a towering 20-inch telescope. Lines of people at night waited to climb a tall stepladder to its eyepiece.

The Andromeda Galaxy was, finally, breathtaking.

But it still was nowhere near as clear as a photograph.

The fact is, our eyes are not meant for looking into space. They evolved to work with things right around us on Earth, things that might affect us. The stars don’t. So it’s a lucky fluke that we can see them at all.

The invention of photography was a turning point for astronomy. Today you can find dazzling observatory photos by the thousands. But what you’re looking at is what you would see if you had eyeballs as big as houses, with light-gathering pupils as wide as garage doors, and electronic retinas thousands of times more sensitive than the retinas nature gave you. And swappable retinas that work in the infrared and ultraviolet where humans can’t see.

So, that dazzling Hubble Space Telescope panorama of the Eta Carinae Nebula is not what you would see even if you were right there looking out the window of a starship. It’s what the camera system of the Hubble would see looking out the window.

Alan M. MacRobert is a senior editor of Sky & Telescope magazine in Cambridge (SkyandTelescope.com). His Star Watch column appears the first Saturday of every month.